- Details

- Published: 04 August 2015

By Heather Campbell

In recent months, organizations and advocates have intensified their calls for a National Seniors Strategy. In particular, the Canadian Medical Association (CMA), under the tireless leadership of Dr. Chris Simpson, has spearheaded a public campaign to encourage the development of a national strategy on seniors care. Similarly, Dr. Samir Sinha and his team have established a website which aims to provide an evidence-based approach to such a strategy.

These advocates and others have crisscrossed the country, written opinion-editorials and advocated directly to politicians. Further, in the lead-up to the election, the CMA is planning a national roundtable on seniors care. Anticipated delegates at this event include representatives from all three levels of government, health advocates, patient representatives, provider organizations and other health care experts.

Ultimately, the CMA and its partner organizations are looking for Canada to have a national seniors strategy by 2019.

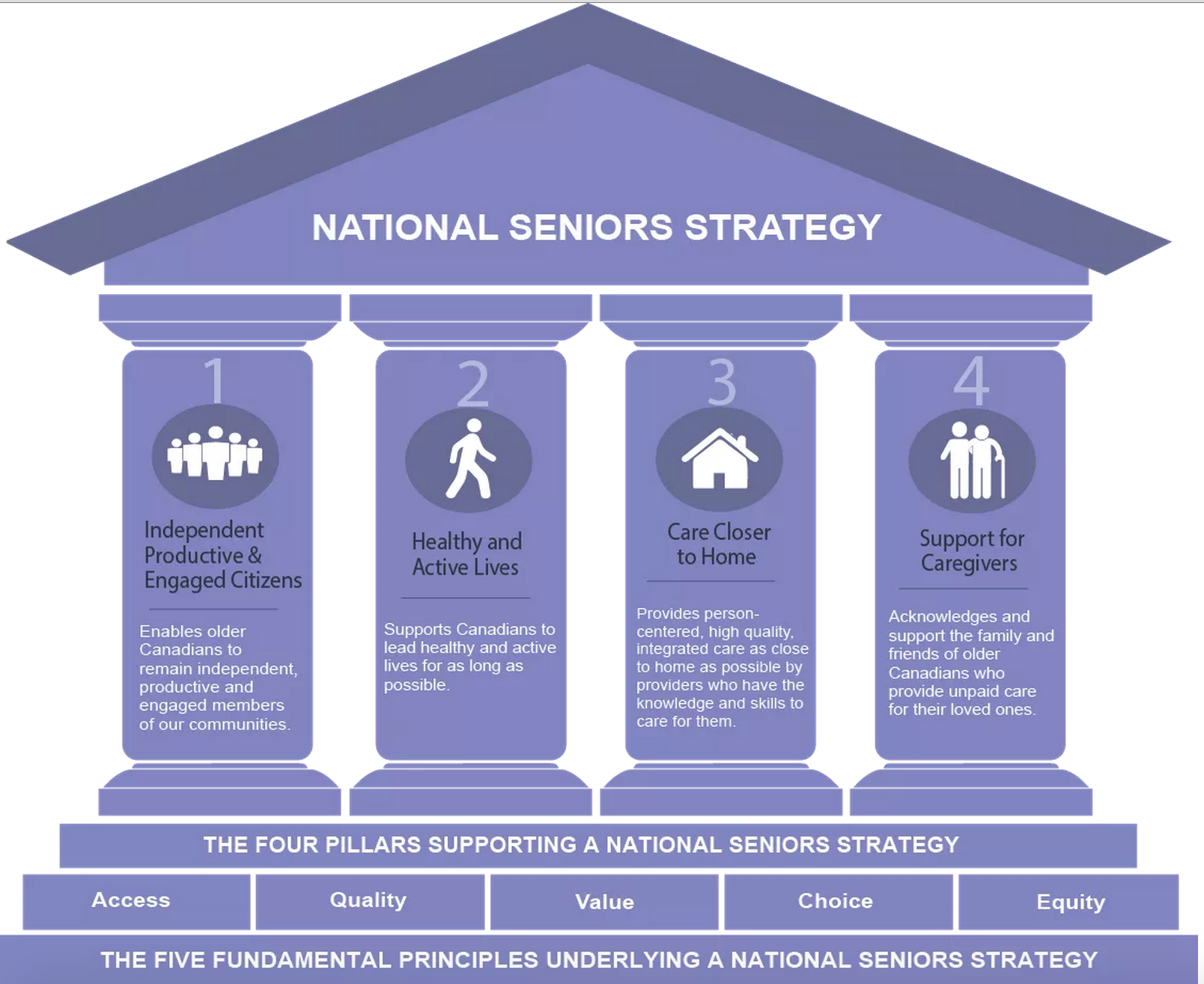

Admirably, Dr. Sinha and his colleagues have produced a brief report on what the strategy should entail. The document sets out the four pillars that should support the strategy, as well as the five fundamental principles underlying it:

This model is a good start. However, in my respectful view, it is missing two important pieces. I suggest that an additional—and the first—pillar should be “Respect for Human, Civil and Other Legal Rights.” Similarly, “Dignity” should be added as the first fundamental principle underlying the strategy. These additions reflect the integration of a rights-based approach into an otherwise health-centric model of aging.

To be sure, the report addresses ageism and elder abuse under the pillar “Independent, Productive and Engaged Citizens.” It states that the government can enable this pillar by:

“Ensuring that we make addressing ageism, elder abuse and social isolation a national priority by ensuring we continue to support activities and policies that continue to value the role, contributions and needs of older Canadians by promoting and supporting volunteerism and other forms of community engagement.”

Again, this is a good start. But in my view, the strategy should couch the issues of ageism and elder abuse in strong rights-based language, rather than taking a soft approach that focuses on volunteerism and other forms of community engagement. Examples of strong rights-based language can be found in HelpAge International’s proposal for a convention on the rights of older people.

Unfortunately, a rights-based approach is frequently absent or lacking in elder advocacy. Instead, seniors’ issues are often viewed through a health lens to the near exclusion of other perspectives. A most striking example is government responses to institutional elder abuse.

Since government responsibility for seniors often rests within health ministries, the dominant discourse tends to reduce older adults to patients, health care consumers and so-called bed blockers. They are rarely viewed as rights-bearing citizens. Deplorable conditions, abuse and preventable deaths in care homes, for example, are characterised as health matters—yet they demand attention from justice departments.

When such alleged rights violations occur, it is usually the provincial minister of health who responds—not the minister of justice. There are endless examples, most recently in Quebec where the health minister issued a statement in response to a cellphone video that captured two care home residents lying on the floor.

The health-centric approach was also evident in MP Claude Gravelle’s well-intentioned private member’s bill for a national dementia strategy. The bill (which was defeated at second reading) would have permitted the federal health minister to appoint an advisory board of up to 20 members, including persons from federal, provincial and territorial health departments, the Alzheimer Society of Canada, and the medical field. There was no mention of legal experts as permanent members.

Another example is the reporting structure of B.C.’s Seniors Advocate. The Advocate reports to the Minister of Health. She also has limited powers, especially when compared to the Commissioner for Older People for Northern Ireland, who has the legislative authority to bring, intervene in or assist in legal proceedings involving the interests of older persons.

A national seniors strategy provides a good opportunity to break down the professional silos separating the health and legal fields in relation to older adults. And by integrating a right-based perspective into the strategy, we can hopefully achieve a greater sense of elder justice in Canada.

Heather Campbell is a Master of Laws student at the University of Saskatchewan.

Heather Campbell is a Master of Laws student at the University of Saskatchewan.

She previously practiced elder law in Vancouver, B.C.

You can follow her on Twitter @SeniorsLaw